The following article provides an overview of these different lenses. The article is a composite of three articles published in 2003 in TypeFace, The British Association for Psychological Type’s quarterly publication. It has been updated with other material.

During the 28 years I’ve been working with psychological type and temperament, I found five very powerful lenses to use in understanding human behavior and what is behind this behavior. Each lens has advantages and disadvantages and brings different information to the understanding of an individual. Each one also lends itself to different applications. These five lenses are: 1) the sixteen types, 2) the four Keirseyan temperaments, 3) the four Interaction Styles, 4) Cognitive Dynamics and type development and 5) Systemic Influences – culture, responses to developmental spaces, Life Themes and organizational culture. In this series of articles, I will briefly explain each lens, how it is used in type identification and type clarification, some useful applications and how it relates to the four-letter type code.

Definitions for Clarity and Common Understanding

What is type? Personality type is a classification system or a way of viewing and understanding personality differences. It is not a grouping of unrelated traits, but rather a framework for detecting patterns that already exist and the processes related to those patterns.

There are two aspects of classification systems to be considered: detection of the pattern (type identification and clarification) and the applications or use of the information as a tool to communicate, effect change, or promote growth.

- Detection methods are judged on their accuracy – how well the method accurately identifies the pattern. Often the detection method gets mistaken for the pattern itself. Type is not the results from the MBTI® instrument or any other instrument. It is a pattern that already exists in nature, but is hard to see directly. Use of the instrument is a help in detecting and calling out or naming that pattern so we can become aware of it and work with it rather than against it. There are other detection methods like projective methods and self-discovery methods. Given the complexity of human behavior, all of them require verification and multiple, related methods often work better than any one method alone. Multiple lenses are also helpful.

- Applications are judged on their usefulness – how well do they work. There are many reasons why an application will work – relevance to the situation; easy to remember; practice; compatibility with the individual’s already held belief systems, models, experiences, vision; readiness on the part of the learner – to name a few.

First Lens – Sixteen Whole Types

Let’s start with what exists in nature – whole patterns. There are many patterns of personality, but sixteen very similar patterns seem to emerge even when different theories are used to explain them. I’m sure there are more, but let’s just stay with sixteen for now. Most type practitioners will agree that there are sixteen types. Yet many don’t recognize that each type is a pattern that has its own theme. It is not the sum of the letters. (When I use the four-letter code as a noun, I’m referring to this type pattern which could be referenced by a name.) To effectively look at type this way, you need tools like thematic, narrative descriptions that have been confirmed and validated. These descriptions can then be useful detection tools. In the late 1990’s we developed some thematic narrative descriptions by asking four people of each type “What’s it like to be you?” and then looking for the themes in their responses. We then wrote the descriptions in the language used by that type using their words, phrases and even syntax. We then submitted the descriptions to other people of those types for what fitted and what didn’t. Dario Nardi1 also generated some very brief themes of each of the types that were not derived from the type code, but from an understanding of the whole pattern. Sandra Hirsh and Jean Kummerow2 wrote some quite complete descriptions of whole types. So far, no instrument has been devised to pick up whole type patterns, although I remember Allen Hammer saying that in the development of Form M of the MBTI® instrument, there was one item that identified ISTJ very consistently and that maybe one day we’d have such elegant items for each type.

The whole-type lens is most useful in detection and verification of the type pattern. For type practitioners, to be able to think at this level is the ultimate goal. To recognize a type by the whole pattern rather than a limited aspect of the pattern is very useful in helping people clarify their types as the practitioner can readily see what is fitting and suggest a description to read for a better fit. To get this level of knowledge takes thinking about type slightly differently and not just looking at the preferences and the characteristics of the preferences or even type dynamics. Notice aspects of the ESFP theme that you can’t quite attribute to a preference in the following excerpt:

“Motivator Presenter – ESFP Stimulating action. Have a sense of style. Talent for presenting things in a useful way. Natural actors – engaging others. Opening up people to possibilities. Respect for freedom. Taking risks. A love of learning, especially about people. Genuine caring. Sometimes misperceive other’s intentions.”1 (p. 10)

The primary application of this lens is self-knowledge and self-leadership as people learn more about themselves by reading descriptions of their type. There are many books that provide this information as well as booklets that go beyond summaries of the preferences. This lens is also useful for coaches as some things are more related to the whole type theme than the other lenses or the more common explanation of the four preferences. Notice the ESFP theme playing out in this excerpt from Dr. Nardi under the heading “Reminders for Personal Growth”:

“… Sometimes it is best to let sleeping dogs lie. When people are avoiding or delaying an action, try to understand why before giving suggestions or helping them make a change …” 3 (p.11)

For other applications, this lens is a bit of overload for the usual recipient of type information – clients and workshop participants, so other lenses often prove more useful.

Second Lens—The Four Temperaments

History and Development. Temperament theory has been around for over 25 centuries in one form or another. Not only the early philosophers but modern scientists recognize that every living being has a temperament, often described in terms such as easygoing, high strung, calm etc. Until David Keirsey published Please Understand Me in 19784, not much had been done with temperament theory except to study children. Keirseyan Temperament Theory has it roots in the works of Ernst Kretschmer and Eduard Spränger in the 1920s – the same time that Jung was writing about Psychological Types. Temperament is different from Jungian typology and did not derive from it. Keirsey developed his modern theory of temperament in the early 1950s, then he came across Isabel Myers’ work in 1958 and linked the two. He found her descriptions of the types with extraverted Sensing (_S_Ps) introverted Sensing (_S_Js) matched so well the descriptions of what he later named Artisan and Guardian temperaments that he found the MBTI® instrument could be used with temperament theory with a high degree of accuracy.

Match of Patterns. The link with psychological type is a match of patterns, not any attempt to make a logical extension of Jung’s or Briggs and Myers’ interpretations of Jung. I think this is best explained with some analogies. It is known that our language and lenses influence what we perceive. Eskimos have many words for snow and perceive many differences in the kind of snow that people from other cultures do not. If I describe snow, I’ll use my lenses to describe it. An Eskimo would describe it differently, yet would recognize the essential qualities of “snow” in my descriptions. I do not have the lenses to see the different kinds of snow until I interact with someone who does. Then I can see it. Another analogy might be of different people looking at a tree. One person says, “It has a tall thick, upright cylinder off of which other cylinders reach out.” Another person might say, “There is a tall, thick trunk, with many branches at the top.” Yet another might say, “There is a trunk which is constructed in such a way that the nutrients are carried up from the roots out to the branches.” They are all describing the same pattern, using different words and with a different focus. The first two have a different vocabulary for describing the structure of the tree. The third one uses the same vocabulary, but is focused on a process that goes on within the structure. And furthermore, the tree and its enduring pattern exist independently of the varied descriptions. So if you have the lens of looking at mental functions or processes, then the patterns you will see are based on those processes and you would tend to group the sixteen types by the predominance of the functions – ST and SF. Isabel Myers wrote descriptions based on Jung’s model and the dominant functions. When David Keirsey read those descriptions he found the patterns of behavior of ESFP, ESTP, ISFP and ISTP, to include essential qualities of descriptions of patterns of behavior that he later called Improviser™. The Improviser™ pattern description derived from the temperament model, not the Jungian one, and had a different focus (likewise with the Stabilizer™ pattern and _S_Js). I remember Mary McCaulley saying years ago that once David Keirsey pointed out the temperament groupings, it made a lot of sense to look at those types who share preferences for S and P and S and J as well as those types who share the Functional Pairs in research.

I have used the temperament model extensively since I learned it in 1975 and have consistently found that when people find their best-fit type, they agree that the corresponding temperament patterns fit them as well.

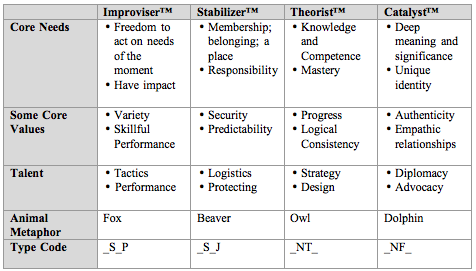

What is Temperament? In 1982, I developed the Temperament Target5 graphic to display the temperament pattern. At the core of the pattern are the core needs of each temperament.

These are like the core of the apple – central and essential to existence. Related and closely tied to the core needs are the core values, then the talents that help get those core needs met and the pattern of some behaviors that relate to the core needs and values.

Understanding this pattern is essential to understanding temperament. Some descriptions of the four temperaments miss the core needs. For example, the Catalyst™ has a core need for having deep meaning in their lives and a unique identity. This need for identity is so strong they often spend their lives in search of it. Yet many portrayals of this temperament focus only on their interest in people. Of course, they are interested in people, but so are other types. The Catalyst™ has a talent for diplomacy, which helps them honor others’ own unique meanings and identities and yet helps them all stay connected. In this way, the talent is the means to “scratch the itch” created by the core needs and values. The Catalyst™ pattern is found in the four types that share N and F in their code. The temperament lens gives us information that the functional pairs of N and F don’t. It isn’t just about iNtuiting and Feeling. The pattern is more than that. The basics are in the following table. (Please don’t take the words as fully descriptive of the characteristic. Do some follow-up reading in the resources listed at the end of the article.)

Temperament Dynamics. There are polarities or dynamics between the temperaments. Each temperament pattern requires different kinds of language, roles, and attention to maintain itself, therefore people of different temperaments have preferences for different polarities. While there is an innate preference for one pole of each polarity, we can choose to shift our behavior from polarity to the other.

The language preferred by Catalysts and Theorists tends to be abstract, referring to concepts, abstract patterns, and symbols. The language preferred by Stabilizers and Improvisers tends to be concrete, referring to the tangible and observable.

Catalysts and Stabilizers tend to prefer affiliative roles of cooperation and interdependence. Theorists and Improvisers tend to prefer pragmatic roles where the focus is on the outcome and independence rather than getting permission. In this sense pragmatic roles are not about practicality, but about a utilitarian approach to doing what works regardless of norms or agreements. Affiliative roles involve some kind of explicit or implicit agreement or sanction before acting.

The shared dynamic between Theorists and Stabilizers in that they both look for structure. Theorists look for conceptual structure like frameworks, models, and configurations while Stabilizers look for more tangible structures like sequences and hierarchy. Catalysts and Improvisers look for motives. Catalysts tend to focus on deep motivations whereas Improvisers focus on the payoff or what is in it for the other person to behave a certain way.

The Uses of Temperament. The temperament lens is very useful in type clarification. Often it can help people sort out instrument results based on responses given from a situational focus or even measurement error. For example, take our ESFP. I’ve known many ESFPs who originally reported ENFP. When asked to self-select according to temperament, they found the Improviser™ core needs, values, and talents really spoke to them. So then, when they took a closer look at the ESFP full type descriptions, they found they did indeed fit them the best. The clue to having them look at the ESFP description is often the pragmatic (do what it takes, ask for permission later) approach of the Improviser™.

The Temperament lens is even more useful in the applications arena. People easily remember the four temperaments, especially when we use the animal metaphors. A major application is in communication. Clients and workshop participants can be quickly taught to identify the themes in others. And they can easily learn to shift their perspectives and speak the language of different temperaments. This single skill will serve them well in their personal relationships, in customer service, in sales, in advertising, on teams, in leadership and so on. Another major application is in career or personal counseling and in coaching. When our core needs are not being met, we have what we call temperament stress. Take our ESFP example again. When in a work situation when trouble-shooting or variation is not allowed and everything is by the book, someone with the Improviser™ temperament will feel bored and trapped and may find ways to avoid their work. We are at our best when we are in a situation where our core needs are met and our talents engaged. Leaders would do well to keep this in mind as they work to create conditions that get the most out of their workers. These applications are just a few of the very powerful ones. We know they work and we know they last. In the fall of 1997 a hospital engaged us to help them with organizational communication. A program was instituted and internal facilitators trained. The program is still going and when we visit them, people still remember the temperaments and the impact the training had on their personal lives. This hospital just achieved the status of being listed as number 78 on Fortune magazine’s top 100 places to work. Their CEO says the work we did with temperament had a lot to do with their success. I encourage you to do a little study and find ways to use this powerful lens in your work with type.

Third Lens—The Four Interaction Styles

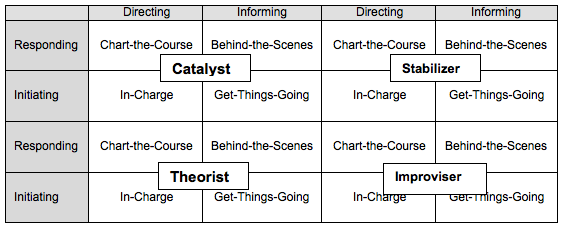

History and Development In 1985, at an APT VI Pre-Conference, David Keirsey introduced the idea of ‘Role Directing’ and ‘Role Informing’ as a dimension of the temperaments, in other words, Directing Theorist™ (_NTJ) and Informing Theorist™ (_NTP). Then at the 1987 Conference he added another distinction – those who tend to ‘Initiate’ interactions and those who prefer to ‘Respond’ to the initiations of others. Using these dimensions we could get to sixteen type patterns with just the temperament model.7,8

We started giving the simple definitions of these dimensions to help people clarify their types. A seasoned type professional had reported ENTP on the MBTI® instrument, yet identified more with F than T. Hearing about the ‘Directing/Informing’ difference in communication style helped her look more closely at ENTP since the Informing style is motivation and process oriented.

Our MBTI® Qualifying Program participants liked the additional information. Also our work with clients showed the ‘Directing/Informing’ dimension to be very powerful in helping them work with conflict. And it was easy to see.

However, I kept finding it harder to explain the ‘Directing/Informing’ dimension. There is such a difference between the extraverted and the introverted version of the ‘Directing’ and ‘Informing’ styles. By using the dimensions Keirsey identified in a matrix, within the temperament, we could identify four different styles within each temperament. ENFJs, ESTJs, ENTJs and ESTPs are the four types that share both ‘Directing’ and ‘Initiating’ dimensions. Then, I began the search for descriptors that would characterize the patterns in a way that was different from type.

To find descriptors I went back to the Social Styles literature I had dismissed as fuzzy temperament descriptions.9,10 I found if temperament filtered out the descriptors that were more temperament related I could use what was left. When I found a descriptor that might work, I put it to the acid test. It had to fit all four of the types that would have a particular style. So for example, ‘In-Charge’ descriptors had to be true for ENFJs, ESTJs, ENTJs and ESTPs.

Eventually, I got some descriptors for a handout that seemed to work. Then, Dario Nardi and I generated some other possible theoretical links – like ‘move toward’, ‘move away from’, ‘move against’, ‘move with’ which fitted references in Bolton and Bolton.10 As a last step, I took the transcripts of the interviews Stephanie Rogers had conducted for our 16 types descriptions and looked for Interaction Style themes. I pulled out phrases, sentences etc. to derive a self-portrait. Dario and I re-worked the first person descriptions and I developed some third person descriptions, which were further validated by many people of each type.

Finally, to write a booklet on Interaction Styles I went back into the previously “rejected” literature on the DiSC® and the Social Styles9-11 to find the roots of the model. I discovered some interesting things. These models seemed to come out of a temperament base just as Keirsey’s Temperament Theory does, however, with a different interpretation.

“The seeds were, in fact, sown for the Interaction Style Model in the 1920s. In 1928, William Marston wrote about the emotional basis for our behavior. John Geier built on Marston’s work and developed the DiSC® instrument. Geier looked at traits and clusters of traits that would help us understand how we behave in the “social field.” Then came a long string of frameworks and instruments that described the social styles of people. These frameworks yielded descriptions similar to Geier’s interpretation of Marston’s work.

“Many of these authors referenced the work of Carl Jung, Isabel Myers, and Katharine Briggs. Their primary focus, in contrast to Jung, was on our behavior, not inner states. Some even referenced Keirsey’s temperament theory. They seemed to not realize they were referencing separate models.

All of these models suggest that these styles or types are inborn.”12

Many of the writings over the years of different typologies have claimed to stem from the four humours identified by the early Greeks: phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile. Their interpretations seemed to be different from Keirsey’s temperaments, but some still had a theme of one Keirseyan temperament.

Match of Patterns. The link with psychological type is a match of patterns, not any attempt to make a logical extension of Jung’s or Briggs and Myers’ interpretations of Jung. In order to understand the Interaction Styles lens, you may need to let go of some expectation that it will match perfectly with J and P or T and F. It doesn’t and, if it did, it would not have value as a separate lens. The dimension of ‘Initiating/Responding’ does match with the MBTI® Step II Extraversion/Introversion facet of ‘Initiating/Receiving’. That facet is the one that has the most breadth statistically and conceptually. Again, the links are with a match of patterns. The patterns exist, the lens just helps describe an aspect of it in a different way.

What is Interaction Styles? Interaction Styles is a model of individual differences – a typology-that is different from and does not stem from Jung’s model. There are some similarities, but the Interaction Styles model brings new information to the understanding of people and helps bring clarity to the Jungian model. Simply put, it addresses the “how” of our behavior – how we interact with others when we try to influence and relate to them. Matches of Interaction Style often determine whether we gain instant rapport with another individual or not.

What is Interaction Styles? Interaction Styles is a model of individual differences – a typology-that is different from and does not stem from Jung’s model. There are some similarities, but the Interaction Styles model brings new information to the understanding of people and helps bring clarity to the Jungian model. Simply put, it addresses the “how” of our behavior – how we interact with others when we try to influence and relate to them. Matches of Interaction Style often determine whether we gain instant rapport with another individual or not.

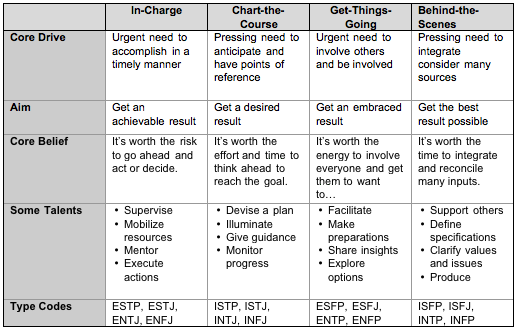

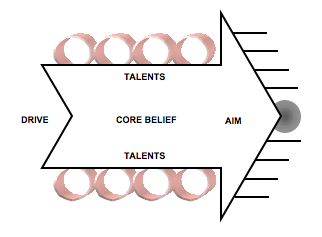

The core of the Interaction Styles Pattern is a basic drive, which we depict as the force behind the arrow graphic. I see this as physical and much of the longitudinal temperament studies point to this. You can see evidence of the Interaction Styles in the way people walk. You can hear it in the way they talk. This basic drive seems to be directed to a kind of outcome or aim. There is also a basic belief behind the style and some related talents.

The basics are in the following table. (Please don’t take the words as fully descriptive of the characteristic. Do some follow-up reading in the resources listed at the end of the article.

Links with DiSC® and Social Styles. The dimensions of each style are very similar to the old task/people dichotomy and the fast pace/slow pace (assertiveness) dichotomy. However, these instruments have a very different response focus – the situation, not the enduring patterns. One problem with most of the ways I’ve seen these instruments used is that they are talked about as if they are enduring patterns yet the instructions say to “have a situational focus when responding”. Thus, the parallels are not direct. Yet the similarities in the descriptions of the patterns are enough that you can relate the four Interaction Styles to the four DiSC® dimensions and to the four social styles for participants. And the model does get at the same kind of information, namely, how we interact with others.

The Uses of Interaction Styles. One of the most powerful uses of this model is in type clarification. This lens clears up many look-alike issues. For example, it can help us understand even more why an ESFP would look so much like an ENFP. Here is the ‘Get-Things-Going’ theme. See how it fits not only ESFP and ENFP, but also ENTP, and ESFJ.

“Get-Things-Going

The theme is persuading and involving others. They thrive in facilitator or catalyst roles and aim to inspire others to move to action, facilitating the process. Their focus is on interaction, often with an expressive style. They ‘Get-Things-Going’ with upbeat energy, enthusiasm, or excitement, which can be contagious. Exploring options and possibilities, making preparations, discovering new ideas, and sharing insights are all ways they get people moving along. They want decisions to be participative and enthusiastic, with everyone involved and engaged.” 13

It can also help differentiate types when one letter is different. Often those with ESTP preferences report as having ENFP preferences on the instrument. Sometimes this is the clue that points them to look at other types beside ENFP. When they look closely at their behavior, it is much more directive and much more “in charge” than either ENFP or ESFP.

Of course, the most exciting application is to help people interact more effectively. People can easily identify the style someone else is using in the moment and adapt to that style.

I also use this model as a starting point for getting to less visible aspects of personality differences such as Temperament and Type Dynamics. As a stand alone, it is a great introduction to personality differences. It is EASY to see the different behaviors and, since these are visible, how they obviously impact working together. It is SAFE since people don’t feel threatened by something that looks deeply psychological.

As mentioned before, I use it to help bridge from the DiSC® and Social Styles model, that they may already be using, to the richness of the 16 Types and Type Dynamics.

Of course, like type and temperament, it helps people make career and lifestyle decisions based on what is more natural for them, serves as a map for coaching others for success, and forms the basis for other training in sales, customer service, working remotely, leadership, teams, you name it!

Fourth Lens – Cognitive Dynamics

This lens tells us how we think about things. That is why I call it Cognitive Dynamics. It refers to the pattern that the letters of the type stand for. However, it goes beyond the notion of the dominant, auxiliary, tertiary, and inferior. The premise is that all of life has natural patterns and the type code stands for sixteen patterns of the eight Jungian functions. Sometimes people refer to this model as the eight-function model. Most of my understanding of this model comes from the work of John Beebe15 who told me years ago that it wasn’t just about what the function is, but where in the pattern the function lies.16

Models, Patterns, Processes

The key to understanding this lens (as well as the other lenses) is to realize that living systems can best be understood by looking at 1) the pattern of the organism, 2) the processes used by the organism to maintain that pattern and 3) the structure-the embodiment of the pattern.

Patterns are configurations that endure over time, even when there is change. The structure changes and the processes are the means to change. The sixteen types are patterns, not sums of randomly connected traits. The functions are the processes. Processes are dynamic. Patterns are static; they remain fundamentally the same.

It is critical not to confuse the pattern with the process. I’ve called this lens out separately from the Whole Type Lens because I want to address the dynamics of the patterns. I think the power of the type model lies in looking at the dynamic interplay among the processes and the roles those processes fill in the personality pattern. We all have access to and use the eight processes. I gave them names to try to capture the essence of them.3

Se Experiencing; noticing changes and opportunities for action; drawn to act on the physical world; scanning for visible reactions and relevant data.

Si Reviewing past experiences; seeking detailed information and links to what is known; accumulating data; recalling stored impressions.

Ne Interpreting situations and relationships; noticing what is not said and threads of meaning; drawn to change what is for what could be.

Ni Foreseeing implications and likely effects without external data; conceptualizing new ways of seeing things or symbols; realizing what “will be.”

Te Segmenting; ordering and organizing for efficiency; systematizing; applying logic setting boundaries; monitoring for standards or specifications being met.

Ti Analyzing; categorizing; evaluating according to principles; checking for inconsistencies; figuring out the principles on which something works.

Fe Connecting; considering others and the group—organizing to meet their needs and honor their values; monitoring for appropriateness or acceptability.

Fi Valuing;considering importance and worth, reviewing for incongruity; evaluating something based on the truths on which it is based;.

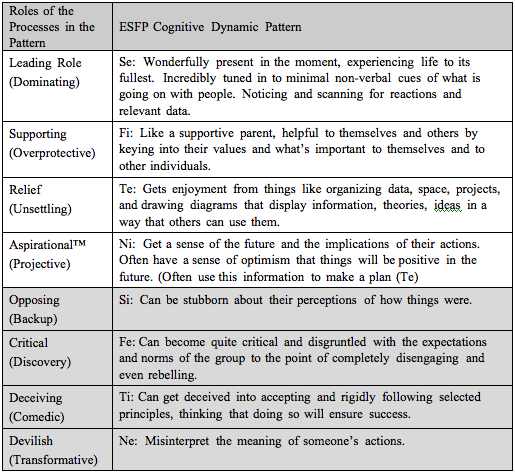

These qualities look different in the light of varying type dynamics which place them in different roles of the personality. Looking at the ESFP example here is how that might look. The first four are the primary processes and most often appear in a positive way in the personality as they become more conscious. The last four are “shadow” processes and thus more unconscious and more likely to be negative. However, the “shadow” processes can and do have a positive side at time.

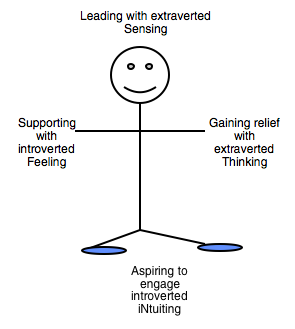

This lens incorporates type development in a very powerful way that can be used in coaching. Beebe describes the dominant and inferior functions as the spine of the personality, with the auxiliary and the tertiary as arms. I like to draw it as a person with the Aspirational role at the feet since this cognitive process is often an unconscious motivator that drives our actions and thus where our feet take us. Beebe says the Aspirational Role process is often the strongest aspect of the personality.18

Uses of the Lens

A primary use is for leadership development, coaching, and counseling. Sometimes people are not engaging more than their Leading Role and the Supporting Role processes and may overuse these processes and under use the others. It helps to have a map for the coaching as well as a way to recognize some of the negative ways the processes can be expressed. For example, an undeveloped or stuck ESFP can be impulsive, selfishly following their own wants and needs and the Leading Role becomes Dominating. Once they gain access to Te and Ni, they become much more centered and find themselves rebelling against societal structures less. The coach can help the individual open up to development opportunities when both he/she and the client have a map for where to go and signposts along the way.

Another important use is type clarification. In our ESFP example, Te plays an interesting role of providing relief and pleasure and we often find ESFPs have very organized closets or are very good at project management. An ESFP friend of mine had her shoes all in boxes and labeled as to color, style, heel height, how long she could stand on them! Clearly, these ESFPs might relate to Judging versus Perceiving if only given the preference scale to respond to.

I have not found this lens helpful in initial type clarification since clients often have difficulty seeing their own preferred processes and can get confused. I use it after I have helped the client find a good fit with their type. Sometimes, exploring this model can help the client decide which of two type patterns fit.

Fifth Lens—Systemic Influences

Living Systems

The fifth lens is not really a single lens, but a recognition that we are living systems operating within living systems and there are other systemic influences beside type that inform our identities and our behaviors. Fundamental to this lens is a premise of holism and gestalt field systems. We come into the world as wholes, not parts that get “assembled” into wholes. We are organized and born that way. The pattern of organization exists and can be described in many ways, some more useful and more accurate that others. The pattern is there to begin with and it emerges in interaction with the “field” or the environment. Thus we have a core self for which the template is there from birth and we have a developed self that results from the interaction of the context or the situations we find ourselves in and the inner push from the core to grow and develop in certain ways to fulfill the pattern. The pattern will be there always, even though it may look like other patterns on the surface. I’ve always been most interested in uncovering this original pattern because I believe nature works better when worked with than when worked against.

Some of the systemic influences come from within the system and thus other models are helpful such as Dario Nardi’s model of Life-Themes. Each of these eight Life-Themes – Physical, Creative, Establishment, Community, Academic, Entrepreneurial, Political, Growth – colors our types. Thus an ESFP with a Growth Life-Theme might look more like an ENFP and one with an Establishment Life-Theme might look like an ESFJ.19 So many varieties of type to enjoy! If you don’t know about these other models, then you can be hindered in your ability to help others clarify their type.

Influences from outside the system are the family, the culture, and organizational culture to name a few. We all behave a little differently in different contexts and we can’t assume someone’s type will rule their behavior in a given context.

So these are the five lenses I’ve found most useful. In my view the competent type practitioner would do well to be familiar with all of them. I use all of them in the background even when I am only using one with my client or my participants. They keep me from over-generalizing and over-stereotyping. They give me more flexibility in helping my clients and more accuracy in helping them find a better fit. I hope you are curious enough to learn some more.

References:

1 Berens LV, Nardi D. The Sixteen Personality Types, Descriptions for Self-Discovery. Los Angeles, Calif.: Radiance House Publications, 1999.

2 Hirsch SK, Kummerow J. Life Types. New York: Warner Books, Inc., 1989.

3 Berens LV et al. Quick Guide to the 16 Personality Types in Organizations. Huntington Beach, Calif.: Telos Publications, 2001.

4 Keirsey D, Bates M. Please Understand Me. 3rd ed. Del Mar, Calif.: Prometheus Nemesis Books, 1978

5 Berens LV. Understanding Yourself and Others, An Introduction To the 4 Temperaments. 4.0.. Huntington Beach, Calif.: Telos Publications, 2010.

6 See www.interstrength.com for more information about the Self-Discovery process.

7 Keirsey, David. Please Understand Me II. Del Mar, Calif.: Prometheus Nemesis Books, 1998

8 Keirsey D. Portraits of Temperament. Del Mar, CA: Prometheus Nemesis Books, 1987.

9 Bolton R & Bolton DG. People Styles at Work: Making Bad Relationships Good and Good Relationships Better. New York: American Management Association, 1996.

10 Bolton R & Bolton DG. Social Style/Management Style: Developing Productive Work Relationships. New York: American Management Association, 1984.

11 Marston W. Emotions of Normal People. Minneapolis: Personal Press [1928], 1979.

12 Berens, LV. Understanding Yourself and Others: An Introduction to Interaction Styles. 2.0 (pp.2) Huntington Beach, CA: Telos Publications, 2008.

13 As above (pp.22)

14 http://www.InteractionStyles.com

15 Harris, AS. Living with Paradox. Pacific Grove, Calif.: Brooks/Cole Publishing, 1996.

16 Beebe, John. Personal Communication at APT X Conference, Newport Beach, California, 1993.

17 Berens, LV. Dynamics of Personality Type, Understanding and Applying Jung’s Cognitive Processes. Huntington Beach, Calif.: Telos Publications, 1999.

18 Beebe, J. Workshop presented by Type Resources in Oakland, California, 2001.

19 Nardi, D. Character and Personality Type; Discovering Your Uniqueness for Career and Relationship Success. Huntington Beach, Calif.: Telos Publications, 1999.